Dear Harbour,

Let us share with You the story of the early years of HATS and how it evolved to become the successful environmental infrastructure it is today. Thanks to the Government’s decision to go ahead with HATS despite great uncertainties, the pollution problem in our dear Harbour was tackled before too late.

A mega-sized project such as HATS naturally attracts attention and controversy. During the HATS planning stage, a key bone of contention was whether to adopt a centralised or decentralised approach to sewage collection and treatment. The centralised option would require the construction of deep tunnels to convey sewage from various districts on both sides of the Harbour to a centralised plant for further treatment before discharge into the sea. The decentralised option, on the other hand, would require constructing advanced sewage treatment works in individual districts, from which treated sewage could be directly discharged into the sea.

There was also controversy on the location of the proposed ocean outfall of the treated sewage.

Centralised vs Decentralised Options

Both computer and physical models were used to test the environmental impact of different levels of treatment and different outfall locations. A decision support system was adopted to help shortlist strategies and evaluate options.

These analyses found that the most cost-effective solution for HATS was the centralised option — an integrated deep sewage tunnel system to collect and treat all sewage from both sides of the Harbour at a centralised sewage treatment plant on Stonecutters Island. A long ocean outfall was planned to discharge treated sewage into the South China Sea to make use of the vast self-cleansing capacity of the ocean, which would do away with the need for a higher level of sewage treatment. The decentralised option was ruled out as it would be greatly constrained by scarcity of land in urban areas.

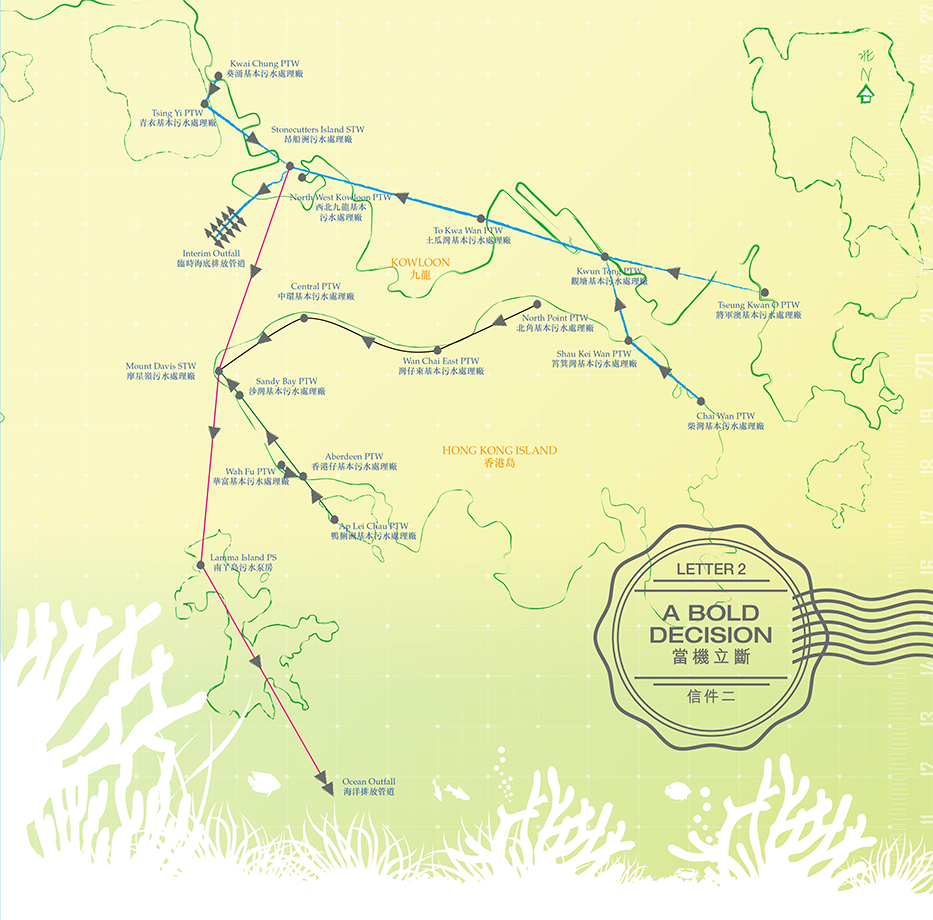

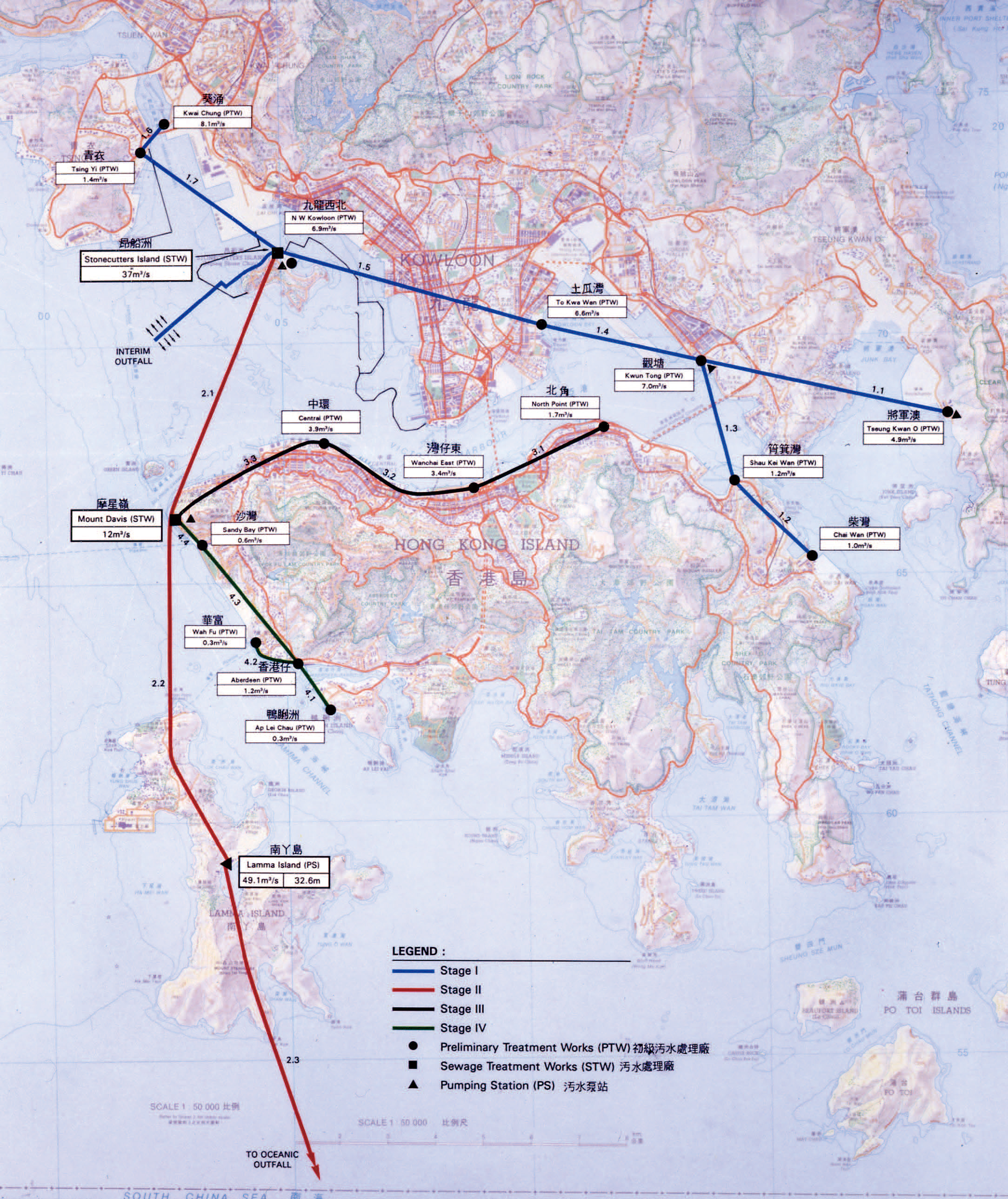

Accordingly, the Government formulated a four-stage conceptual implementation plan for HATS, still called Strategic Sewage Disposal Scheme (SSDS) then. Further studies were necessary to confirm the technical feasibility of the deep sewage tunnel system and the centralised treatment plant, and pave the way for detailed design and construction. We promptly moved to engage a consortium of consultants to conduct comprehensive site investigation and engineering studies beginning in June 1990 for completion in 1992.

Investigation was conducted to look into the performance of diffusers of the ocean outfall with the aid of a physical model. Vertical and inclined boreholes as well as geophysical method were used to identify the most suitable founding stratum for the ocean outfall.

Original proposal of the Strategic Sewage Disposal Scheme

As later developments would show, the ocean outfall originally planned under SSDS was overtaken by events and not implemented, whereas the other stages in SSDS were duly carried out and became Stage 1 and Stage 2A of HATS today.

Funding was secured too. Stage 1 of HATS required around HK$6 billion for capital cost, while its operation and maintenance would call for a recurrent expenditure of HK$300 million per annum. Government decided to fund the capital cost from its Capital Works Reserve Fund, with the annual recurrent cost being met by a new Sewage Services Charging Scheme based on the “polluter pays” principle new to Hong Kong. The charging scheme was made possible by the Sewage Services Ordinance (Cap. 463) enacted in 1994, which enabled DSD to start collecting sewage charges from 1995 onwards.

DSD proceeded in July 1993 to engage consultants to carry out the detailed design and construction of HATS Stage 1, so as to tackle harbour pollution as soon as possible.

Mainland Concerns about Ocean Outfall

While engineers were working on the preliminary design of Stage 1 works, the project caught the attention of the Mainland authorities who were concerned that the water quality of Lema Channel in China waters would be affected by the discharges of HATS. At about the same time, the Government commissioned a study named “Review of Strategic Sewage Disposal Scheme Stage II Options” in July 1994. An International Review Panel (IRP) was set up, also in 1994, to advise the Government on the Stage II options review study. The IRP comprised three renowned environmental experts including one from the Mainland.

After much deliberation, the IRP concluded that chemically enhanced primary treatment (CEPT) ought to be the minimum level of treatment at the Stonecutters Island centralised plant. Three outfall locations were proposed — East Lamma, West Lamma, and Lema Channel — subject to the findings of a joint Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study commissioned by Hong Kong and Mainland authorities in May 1996.

The IRP review marked the beginning of a prolonged period of communication between the Hong Kong Government and Mainland authorities on various outfall and treatment level options of HATS.

The Government commissioned the Review of Strategic Sewage Disposal Scheme Stage II Options in 1994

Decision to Press Ahead

Despite these longer-term uncertainties, the Government decided to abate the serious harbour pollution problem as soon as possible and press ahead with the design and construction of Stage 1 of HATS, previously known as SSDS Stage 1.

The scope of work of HATS Stage 1 included: A deep tunnel system at a total length of 23.6 km to collect sewage from Kowloon and Hong Kong Island North East, covering Preliminary Treatment Works (PTWs) in Kwai Chung, Tsing Yi, Kwun Tong, To Kwa Wan, Tseung Kwan O, Chai Wan, and Shau Kei Wan; upgrading works at those seven PTWs; a centralised chemically enhanced primary treatment works on Stonecutters Island; and an interim outfall at 1.7 km off Stonecutters Island to discharge treated sewage.

In July 1993, DSD engaged consultants to carry out detailed design and construction of HATS Stage 1. The target was to complete the works before July 1997 when Hong Kong would become a Special Administrative Region of the People’s Republic of China. As things turned out, Stage 1 was successfully commissioned in 2001, after quite a few twists and turns.

POSTSCRIPT

“We shall work continuously with our colleagues to maintain the water quality in Victoria Harbour, progress with the times to make Hong Kong’s water quality even better, and enhance our culture of water excellence.”

“Sludge from HATS used to take up considerable landfill space which was an issue. Ever since T · PARK began working with HATS to turn its sludge into energy, it not only generates sufficient electricity for the park facilities but also surplus electricity to feed into the city grid. The ‘waste-to-energy’ loop has made Hong Kong more environmental too.”

WONG Kam-sing

Secretary for the Environment,

Environment Bureau